3.1 HIGH SCHOOL

I entered Wichita Falls Senior High School at midterm, January, 1938, because sometime during Second or Third Grade my mother had convinced the principal that I was so brilliant that I should be "double promoted" and I had been summarily removed from one schoolroom and escorted to a new one filled with older, bigger, and hostile kids. I'm sure she had in mind doing it at least one more time, but she never got around to it again. High School was a whole new world, daunting if not intimidating to a naive kid who was thrust into it half a year early.

Wichita Falls Senior High was one of the largest and best high schools in Texas. It was an impressive physical plant-- it had to be to contain the 2500 students enrolled -- and it was manned by a staff of mostly competent, highly dedicated teachers and administrators. The Principal, Mr. S. H. Rider, was clearly but quietly in charge. He was absolutely unflappable, always immaculate in a suit, white shirt, and tie even at 100 plus degrees and no air conditioning. He was firm but friendly, called everyone by their first name, and no one ever called him anything but Mr. Rider, even behind his back.

That first semester the students, especially the seniors, were impressively mature compared to the children I had left in junior high. Lynn Ruth Bagget was already there and looked like the movie star she almost became. Although I had known her since I was five and was almost killed on the way home from her parent's store, I wouldn't have dared to speak to her if I met her face to face in the hall-- prostrate myself maybe, but speak, never. The football players I had followed for two years up to the State Championship Game were frequently the center of throngs in the hall, and they congregated on the sidewalk in front of the school to smoke cigarettes before school and during the lunch period.

The althletes were huge. Art Goforth was about the size of King Kong and looked a lot like later artist's impressions of Neanderthal Man, prognathous jaw covered with a permanent five o'clock shadow beneath a simian-like brow ridge. Odell Damerall was tall and almost thin, but radiated strength like a steel cable. Both of them were graduating, but the thought that I might be practicing football with the returning veterans was exciting, if more than a little intimidating. The likelihood of actually playing with any of those demigods was remote; in the football factory set up at Wichita High, one typically played on the "C" Squad or Sophomore team the first year, the Rowdies the second year, and the Coyotes (the varsity) your senior year. Some exceptional football players were elevated to the Coyotes for their junior year, but I never heard of anyone so talented they made the varsity Coyotes their first year. In those days we only had eleven grades, with three years of high school. The year before I graduated, the Texas Interscholastic League changed the eligibility rules and created all kinds of opportunities for creative coaches and imaginative administrations to win consistently.

There was so much less regimentation compared to junior high that everything seemed chaotic. Before classes began in the morning, the rich kids would arrive in their own cars, the girls sensibly and the boys with a flourish, like cowboys bringing their horses to a sliding halt from a full gallop, fish tailing and throwing gravel. The middle class kids were dropped off by their mothers or, more frequently, by their fathers on his way to work. The poor kids came by foot, bicycle, and bus, many of the latter from miles out in the country.

Students began arriving at least an hour before classes began, the reasons for which varied. Many of the country kids were at the mercy of the school bus schedules, some dependent on their father's work schedule, and others for social reasons. The sidewalk in front of the school was the last legal site for smoking, and many of the boys congregated for a cigarette swiped from their father's pack on the way out the door or from their own packs carefully concealed from their parents. We never smoked pot; we called it marijuana if we called it anything at all, and only the Mexicans used it. The same went for the hard drugs. We hadn't even heard of heroin or cocaine; cigarettes and alcohol satisfied our unsophisticated tastes.

Some kids arrived early for another reason, romance. The large building, with its numerous stairwells, quiet corners, and secluded nooks and crannies provided almost unlimited sites for assignations of varying intensity. Some couples, whose parents would not let them date, established territorial rights on specific, particularly private locations that both students and faculty -- the latter tacitly -- knew and respected. I suspect there were more than a few cross religion and cross racial marriages (excluding blacks because of segregation) forged, to the surprise of both sets of parents, in the stairwells of Wichita Falls Senior High School.

The few minutes prior to the beginning of classes were chaotic. The halls were packed with students and teachers, the latter to attempt to maintain some semblance of order and the former headed in all directions talking at the top of their voices. When everyone reached their first class and the bell rang, the halls were deserted and the silence was deafening. Fifty five minutes later the bell rang and pandemonium reigned for five frenetic minutes. Lunch was, by necessity, in shifts. During your lunch period, you went to the cafeteria, went through the line and selected your nutritionist-chosen meal, if your parents or you could afford it. Otherwise, you ate a fried-egg sandwich or something equally appetizing out of a paper bag brought from home. The lucky ones were the ones who lived near enough to school to go home for lunch. Only the rich kids with cars could hit the hamburger joints for lunch; we figured they did some other things more exciting in their cars during lunch.

3.2 High School Football

The reason for the huge enrollment, accompanied by overcrowding and excessive commuting time, was the refusal by the voting adults of the city to provide funds for construction of a second high school in Wichita Falls. Every time a School Bond authorizing construction of another high school appeared on the ballot, it was soundly defeated because it would “dilute the talent" on the football team. Wichita Falls had a population of approximately 25,000 at the time; the other towns we competed with for the District Championship (Burkburnett, Electra, Vernon, Quannah, Olney and Graham) were much smaller, and most had barely enough students to qualify for Class AA, the highest ranking at the time.

As a result, the smaller schools had fewer boys available for the football team, fewer and lower-paid coaches, less money for equipment, and much lower attendance, thus much less money for the extras. Wichita Falls had a quality athletic setup, better than most of the colleges I visited when I was being recruited as a senior, including TCU. There was a large classroom/projection room adjacent to the immaculate, brightly lit dressing room. Equipment for the varsity was state of the art, new every year, and comparable if not identical to that at major colleges. The Rowdies were issued the previous year’s varsity uniforms and equipment; the "C" squad had to make do with two-year old gear. Wichita Falls could afford the best and all the coaches needed, and, in addition to the practice field behind the high school, Coyote Stadium at the edge of town had a full-time groundskeeper/maintenance man and averaged 6,000 to 8,000 paid admissions per game for the season.

Not surprisingly, the Coyotes won the District IIAA Championship most years. Most years was not good enough; they were expected to win every year, and if they didn't everybody in town was madder than hell and wanting to know why. There were always plenty of experts ready to fix the blame in newspaper columns, letters to the editor, and in barber shops, coffee shops, and filling stations.

People in the smaller towns were as, if not more, involved in the fortunes of their high school football team; it was the symbol of civic success or failure, and everyone in our district HATED the big city Wichita Falls Coyotes. Beating the Coyotes made their season, even if they lost every other game. That guaranteed every team would be psyched like Samurai warriors when they played Wichita Falls. Even with all odds against them (superiority in numbers, talent, coaching and equipment), the country boys would occasionally eke out a win on sheer determination. The real problem usually began in the BiDistrict game, (the first round of the playoffs for the State Championship) pitting the winner of District IIAA against the winner of the district in the Panhandle. Amarillo was about the same size as Wichita Falls, also had only one high school, and their football team -- appropriately named the Sandstorm or "Sandies" -- dominated the smaller towns in their district even more thoroughly than the Coyotes did theirs. Unfortunately, the Sandies usually beat the Coyotes and the season was over.

When the game was in Amarillo, the excuse for losing was always the altitude: Amarillo was on the "Caprock" (Balcone's Escarpment) and several hundred feet higher than Wichita Falls. Supposedly, football players from lower elevations did not have the stamina to compete with the local players with their acclimation advantage. (I don't remember what the excuse was when we were trounced in Wichita Falls in alternate years --probably those kids from the higher altitude of Amarillo had even more stamina when they played at lower elevations.) If we could get by Amarillo, or even better, if some team in their district sneaked by them, it was usually clear sailing to the State Finals.

High School Football was so big that the Fort Worth & Denver Railroad ran a Special Train to most out-of-town district games and all playoff games; sometimes more than one was required, especially for the latter. Most of the high school kids would be aboard and the band, in uniform, rode free (paid for by the school or by courtesy of the railroad) and provided impromptu music to whip up enthusiasm. However, most of the riders were adults, in varying degrees of sobriety but a consistent peak of support. The Class AA State Championship was always played in the Cotton Bowl in Dallas and it was usually filled to near capacity.

Enthusiasm for and support of high school football was not restricted to Class AA; they played to State Championships in Class A and B (later in Class AAAA, AAA, AA, and A and to Regional Championships in Class B), all attended by more than 10,000 spectators. Years ago there was an expression overused by the media, "There are two major sports in Texas, Football and Spring Football." There was no high school baseball program; it would have interfered with spring training, and most of the good athletes played football. Only kids too small for football went out for track; basketball ball was okay for backs and, especially, ends because it helped with ball handling and pass catching and was played in winter-- the only time the football team wasn't practicing.

To students at Wichita Falls Senior High School, football was not the only thing going on, just the most important. (Unfortunately, perhaps, it was the only thing of importance to most townspeople). There was an excellent orchestra. Thanks to my mother's insistence for at least eight years that I take violin lessons, I became 1st violinist soon after signing up for orchestra, carefully concealing my aberration from my contemporaries on the football team, and failing to mention my football connections to the nice young lady who directed the orchestra. When I showed up for orchestra practice one day with a finger so grossly swollen that I couldn't play, the cat was out of the bag. When I confessed that I had hurt it at football practice, the director said something to the effect "Albert, you're going to have to decide between football and music". That was not a difficult decision. I put the violin in its case and have never played one in the ensuing 60-plus years.

There were other major interests besides football: boys in girls and girls in boys. If there was any interest of boys in boys or girls in girls, we heterosexuals didn't notice it. I entered into that activity with great enthusiasm, but with several limitations. Football practice took considerable time, and working 40 hours a week at the Western Union on nights and weekends cut down on the time available for dating. But my most severe limitation was the lack of a car. I spent a lot of time with girls in the stairwells, but was dependent on friends who had their own or could get the family car and asked me to "double date" with them for real dates. Those were real prime times; I had to take "time off" from the Western Union, to be made up later, so I tried to get the most possible from every date. Some of the girls, unaware of my time constraints, were put off by what appeared to be my impetuousness.

I didn't resent not having a car and having to work all the time; that was just the way things were. Some people had money and didn't have to work, and others didn't have money and had to work like hell to get along. I knew the only way I was ever going to have anything was to work for it; there was no chance I was going to get anything the hard way -- by inheriting it. If you think the easy way to get money is by inheriting it, try it. The Stiles family figured that out long before I did and always had family businesses going. They did not like to work for wages; they preferred to keep all the profits themselves, including paying the kids less than the going wage. Audie and Jimmy were happy with the arrangement, they made a lot more money than most kids; I occasionally cashed in on their bonanza after they opened a florist business.

My routine through most of high school was: ride my bicycle to school, arriving about 7:30 for a quick meeting with my current girl friend on the back stairs, classes all day, football study hall the last class period, football practice until almost dark, ride the bicycle home for a quick dinner and change into the Western Union uniform, and deliver telegrams by bicycle until midnight. Weekends were when I racked up the hours. I'd be there at 7:00 AM when the Western Union office opened on Saturday morning and work until midnight if allowed, to finish off the 40 hours plus a little overtime at time and a half if I could sneak it by. Saturday mornings were a little tough during the football season, especially if we had played away from home and didn't get home until 1:00 or 2:00 AM. I'd be pretty stiff pedaling the bicycle to the office

and on the first few runs, but I'd soon loosen up and be ready for the day.

I loved Sundays; that started a new week and I was there, in uniform, bright-eyed and bushy tailed, when they opened at 9:00 AM. There was much less business, and I could get in 12 to 14 hours of fairly relaxed work to get off to a good start on the week. Also, middle-aged and older ladies felt sorry for that "poor messenger boy who has to work on Sunday" when I delivered

telegrams or packages and the tips were much better. Holidays were even better; I would have fought for the opportunity to work on Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year's Day. Christmas was the real bonanza; if you could deliver a Western Union Christmas Greeting while a family was opening gifts or, especially, eating Christmas Dinner, there was no telling what you might walk away with. (It helped if the weather was bad; rain or sleet was good, but snow was best: there you were in your uniform, wet even with your poncho, and your nose running just a bit). I've had two or three Christmas Dinners in one day at the insistence of customers, and when too full to eat anything else, I'd refuse further offers "because I had to deliver the rest of the messages". That often elicited an outburst of sympathy and sentimentality, as in "Honey, give that poor boy who has to work on Christmas a nice tip."

I had a good thing going at the Western Union all through High School for one important reason. Johnny Bates, a small man with a large heart, was the Dispatcher (meaning he decided who worked and when) and he "took a liking to me" and took care of me. Probably because I was a boxer (and had a reputation as a street fighter who could take care of himself) and a football player, Mr. Bates sent me on most of the "whorehouse runs". Those involved trips to Lake Street, the open Red Light District, where the price of sin was $2.00, but negotiable; various "hotels" on Ohio Street, such as the Dallas Rooms; and other, better addresses occupied by more exclusive and expensive call girls. The one thing, other than their profession, they had in common was they ALL sent money to SOMEONE: child, parent, pimp or, hopefully but unlikely, for their own retirement. Whatever the reason, they would call the Western Union and ask for a messenger to pick up a money order. I would enter the seamiest sites in Wichita Falls, make out the money order and walk out with several hundred dollars in cash in my pocket. I had a few disquieting experiences; once I was walking down the hall in the Dallas Rooms and saw two guys run out of a room with an open door, one wiping a long knife on his handkerchief. I glanced into the room as I walked by, and there was a man on the bed with his throat slashed. I kept walking; it was none of my business, and it didn't even make the newspaper the next day. I never made big deal of it at High School, but I probably knew every whore in Wichita Falls on a first name basis by the time I was 16 years old in a business relationship (mine, not theirs).

High school was not all hard work; for the first time the courses were interesting and the teachers were knowledgeable. There were a dozen members of the English Department, most of whom had Master’s Degrees. The Department Head was Louise Lipscomb, a pudgy, cheerful little cherub from whom I took at least one course. I think I also took courses from Nell Sammons, but I remember best Miss Ida Jane Collins and Eileen Collins(no relation either by birth or personality). Ida Jane was a tough little lady who, most of the time, controlled her class. I loved deviling her in a way she had trouble coping with, by knowing more than she would really like a student to know about whatever subject in literature we were studying at the time. Eileen Collins was a sweet, gentle lady and I could not do anything to upset her. I just wanted to please her and I busted my butt to do so. Butter would not have melted in my mouth when I was in Eileen Collins' class.

The Social Sciences Department was probably also outstanding, even by modern day, first class high school standards, twelve of the fourteen faculty members had Master's Degrees, the two who didn't were the Band Director and the Basket Ball Coach (they had to teach something). Three courses in history were required for graduation, from a choice of Ancient, European,

American History and Civics. Economics and, of course, Texas History were available as electives.

Mr. Didzun, who wore a Hitler-like brush mustache, taught Civics. He was a veteran of The World War and one of the most enduring experiences of my life was sitting in his Civics class and listening to the radio as Adolf Hitler justified the impending "liberation" of the Sudetenland. It was in German, but Mr. Didzun provided virtual simultaneous translation. I was greatly impressed by his ability to understand German on the radio and immediately translate it to English. He was probably the first real intellectual I had ever known. But I still remember the "goose bumps" when, at the conclusion of Hitler's tirade, Mr. Didzun said "Ladies and Gentlemen, you have just heard the beginning of the most horrible war in the history of mankind”.

We sat in Mr. Didzun's class and listened, with simultaneous translation courtesy of O. J. Didzun as the Nazis "liberated" Poland, Czechoslovakia, and continued to rape the underbelly of Europe, while Neville Chamberlain carried his bumbershoot between London and Berlin, always with studied British understatement, proclaiming the situation was under control and we would, indeed have “Peace in our Time.” Mr. Didzun was not having any of it, predicting with what seemed to me uncanny accuracy Hitler's next move. I've often wondered what such a brilliant man was doing teaching Civics in a North Texas High School when the whole world was going crazy and could have used his expertise.

There was a Natural Sciences Department, offering courses in Biology, Physics and Chemistry. I know I took biology courses from Mr. Morris and William T. Falls. The event I remember best about Mr. Falls was my pet bull snake, taken to school at Mr. Fall's request, biting Mr. Falls as he demonstrated to the class that "bull snakes didn't bite, they're constrictors". That was after he had trouble getting the girls and some of the boys to touch its skin to prove that snakes were not slimy. I don't know what got into that sucker to cause him to defy the canons of herpetology and commit a social gaffe of considerable importance. Maybe he just didn't like Mr. Falls, but Mr. Falls never forgave me; he never actually accused me, but it was my snake.

I had sneaked that bull snake into school, wrapped around my waist and covered by my shirt, lots of times. He seemed to like the attention when the more adventuresome kids gingerly stroked him. And he did get me a lot of attention, especially from the girls, when I pulled his head out the front of my shirt. It was a great phallic symbol with all sorts of biblical connotations, Eve and the serpent offering the apple as temptation. I wish I had been clever enough to have offered the girls an apple as I showed them my bull snake.

I took Chemistry from Mr. F. M. Lisle and learned enough to get through the first and most, but unfortunately not all, of the second semester of freshman chemistry in college without opening a book. My mistake was in not realizing when it was time to open a book. Maybe if I had gone to class I would have recognized when they got beyond what Mr. Lisle had taught me, but I thought he had covered the entire subject. I carefully avoided physics, taught by a Mr. Brown who had the reputation of being as dry as his subject and as tough, too. (Pat –later to be my wife-- took it, the only girl in the class, and loved it, perhaps because she was the only girl in the class).

Seven of the ten faculty members in the Mathematics Department had Masters Degrees; two who didn't were Ted L. Jefferies, the head football coach, and Joe Reed, my junior high coach my last year. The other was "Leaping Lena" McConnell, her nickname based entirely on alliteration; she was a rather plain lady who almost certainly hadn't skipped, let alone leaped in

years. Four and one half credits towards graduation could be earned and regular math subjects could be supplemented by advanced courses. The regular curriculum included Algebra, Plane Geometry, Solid Geometry, Commercial Arithmetic (probably taught by the coaches) and Advanced Arithmetic (probably Advanced Mathematics such as Trigonometry and Calculus in modern parlance).

I liked Math and considered myself sort of a whiz at it; later, in college, I decided I was mentally incompetent in all of it except when dollar signs were in front of the numbers. But in high school I took all the courses offered in algebra and geometry and remember having Lena McConnell, Beatrice Morgan, Ella May Underwood and Fanny Vance as teachers, but I have no recall of what courses I took from whom.

I avoided Manual Training, but did take a couple of courses in Mechanical Drawing, just to see if I might rather be an architect than a surgeon. Interestingly, W. W. "Hoot" Gibson and

Scott Williamson, two of my Junior High Football coaches, were the instructors. Unfortunately, I did not take any foreign language courses; Spanish and Latin were offered and both would

have helped me later. I was smart enough to take a year of typing, one of the few boys in the class, and it has been of immense value over the years.

Although I don't think I realized it at the time, I was actually more interested in the subject matter than in the social aspects of high school. That is not to say that I did not have friends; I had a lot, both in and out of football, and I LOVED the girls, both as girl friends and friends. There were a lot of both sexes I didn't care for and some I detested; I'm sure there were at least as many that felt the same way about me.

My problems with the social aspect began with growing up poor with no exposure to the "social graces"; my mother never went to a Tea at the Country Club or Bridge at Faculty Wives in her life. Gospel Singing and Dinner on the Grounds, maybe, but not a night at the Symphony; having family friends over for Sunday Dinner, but not a standup buffet for 40. "Working People" in the 1940's simply had no concept of what the wealthy, and even middle-class, did for entertainment. I'm sure the latter groups were even less cognizant of what the "poor folks" were doing. If the kids of the wealthy had stayed within their social experience, the middle class within theirs (with a little sneaking in and out by both), and the poor kids in their own social strata, everything would have been in the vernacular of the time Hunky Dory. However, it did not always work out that way in the melting pot of Wichita Falls Senior High School. Some girls from the less privileged families were so bright, had such outgoing personalities, or were so beautiful they moved up in the social pecking order, even without cars of their own or clothes from Niemann Marcus in Dallas or the leading department stores in Wichita Falls. Not many won beauty contests and Hollywood screen tests like Lynne Ruth Baggett, the School Beauty my Junior Year, but a lot of them were welcomed and married into the Country Club Set.

However, the surest route to upward mobility in a one high school Texas town in the late 1930's and early 1940's was to be male and on the football team; you didn't have to be a star or even a starter, though both helped proportionately, but it had to be known that you were “on the team.” To comprehend this, it is necessary to understand the mindset of Texans; every fall Friday night was a shootout with the white-hatted cowboys from your ranch against the outlaws in the black hats. Bankers, oil company executives, and other leaders of the business community were delighted when they could say to their associates something like, "we may be in real trouble on Friday; my daughter's boy friend, he's on the team you know, told me that the center (identified by name of course) jammed his thumb in practice and may not be able to snap the ball." Now that got the attention of everybody at the table at the weekly luncheon of the Rotary Club, quickly spread through the dining room, and was disseminated throughout the city before close of business that day. Unfortunately or not, 16 to 18 year old boys were much more important than the mature, or perhaps immature, adults.

Some kids from the wrong side of the tracks were smart enough to take advantage of the situation. Curtis Holder, a gifted broken-field runner my junior year, married the daughter of the owner of a plumbing company immediately after graduation and entered the business without bothering to go to college. McCharles "Smokey" Huff, after starring at the University of Texas, married Mary Lea Buchanan and subsequently managed her father's stationary store. Even though David Wright was no great shakes as a football player (he was on the team) married Norma Gorman and subsequently ran the large independent oil operation established by her father until his untimely death. Jimmy Castledine secretly married Lois Jean Underwood before graduation and capitalized on the Underwood family’s wealth as ranchers and oil operators, along with his reputation as an All State football player, to be elected the District Attorney in Wichita Falls.

I seriously considered that alternative. I had, for high school, a relatively long relationship with June Young whose father was a partner in Sheppard-Young Cleaners, the largest cleaning and pressing business in Wichita Falls. Mr. Young was also, as most successful business men were in those days, an independent oil operator. I liked all the Young family, especially June. She was a tiny girl, not beautiful but attractive, and wore gorgeous clothes. She probably had everything cleaned and pressed at Sheppard-Young Cleaners after each wearing. She also was a genuinely nice person; I can't remember her saying or doing anything unkind. Her parents were just as nice. They lived in a large, comfortable, but unpretentious, house in a nice, unpretentious neighborhood. June had her own car, not new or a convertible but nice, clean and conservative. June liked to pick me up at home and take me to school, even though she lived within easy walking distance of school, and waited until after football practice to take me home. I had free run of their house and they trusted me completely with their daughter. They were also totally understanding, but not condescending, of the necessity that I work.

I think the problem was that they were TOO nice, to the point of boredom. As it gradually became clear that they expected me to really become a member of the family, with not very subtle hints about my getting into the business, I began to wonder what I was getting myself into. At sixteen, I wasn't sure I wanted my future ordained, even if it would obviously be better than anyone in my family had attained. The more I thought about it while riding my bicycle on night duty at the Western Union, the less appealing it became. I gradually cooled it with June by starting to date other girls, to her dismay at my unfaithfulness. I regret that I didn't have the guts to sit down with June and her parents and say, "this is not the way for me; I have to do it on my own even if I fail." Who knows, they may have liked me enough to accept me on my terms and even encouraged me.

I don't know how Sheppard-Young Cleaners or the Young Independent Oil Company prospered without my inspired leadership. I was saddened to hear from Marjorie Page Kelly many years ago that June had died from uterine cancer. The important point about the Youngs was that they were one of the most genuinely nice families I’ve known. Not one of them ever indicated to me that they were even disappointed that I had "jilted" their daughter and not entered the family business.

Part of my problem, both pre- and post-June Young, was that I was hooked on Band Majorettes. I dated most of them, starting with Betty Lou Plunkett, shortly after we entered high school. Majorettes all had gorgeous figures, a requirement for selection, and their skimpy costumes revealed them. They were real athletes, all their practice of high stepping and baton twirling kept them in great shape; but they all had calloused hands from handling the batons, no matter how much Jergen’s Lotion they used. Betty Lou's father delivered milk for a local dairy in a horse-drawn wagon. There was no stigma to that; I worked a couple of summers as a helper on a horse-drawn ice wagon before I got on at the Western Union. The ice came out of the freezer at the ice house in three-hundred pound blocks; I'll never forget the pride when I first lifted a three hundred block off the floor, straddling it and carefully hooking the "Ice Tongs" in at the exact center of gravity. You then used ice picks to cut it into one hundred pound blocks before you loaded it into the wagon, shoving most of the blocks to the cool back of the wagon so they wouldn't melt. As we "ran the route", we'd look up at windows to see who wanted ice and how much. The ice company provided cards with "25" at the top and "50" at the bottom on one side and "75" on top and "100" on bottom on the other side, with the lower figures upside down. The hundred pound blocks had four indentations, allowing one to separate them into 25, 50, or 75 pound segments with an ice pick. When we saw the upper number in a window, we sank the tongs into the center of the requested amount, hoisted it onto the leather carrier on our back and carried it into the dwelling and to the Ice Box (Needless to say, that was before the advent of Refrigerators). Carrying a hundred pound block of ice up the stairs of a garage apartment when you were a hundred and twenty five pound Junior High School student was both a challenge and a character builder.

Betty Lou's family were from that background; if you have a job, work hard and you might keep it. I'm sure Mr. Plunkett was up by 4:00 AM six days a week (he called me once at that time when he had heard rumors --unfounded of course -- of his daughter's and my relationship). They lived on the outskirts of town, probably had a small truck farm, and were good, solid people. Betty Lou assumed that we would get married after High School, but that was not exactly what I had in mind.

I’m not sure when I started "going with Flora "Tiny" Haynes. I do remember that I was at a party in the Low Rent District and won a walk around the block in "Spin the Bottle" with a girl I had never seen before. WOW, life was never the same again; I still can't believe how much I matured in a walk around the block without anything other than my feet touching the ground, and they only occasionally. She had ways of kissing I had not only not heard of but were way beyond my imagination. I didn't learn until school started that she was a majorette, and that I was neither the first nor the last she had initiated into the adult world. Unfortunately as far as I was concerned, she was always in control and knew precisely when to stop, leaving me frustrated from smelling the flowers but never tasting the fruit. Learning that Tiny Haynes was not totally innocent did not drive me from her in righteous disgust; instead, it had the opposite effect, I was after her like a white tail buck in rut after a doe for months. However, she was always way ahead of me in the mating game and I went something like 0 for 50 in the box scores.

Other majorettes were friends, but not really girl friends: Beatrice Michna, Betty Jo Lewis, Jean Brashear, and Virginia Carpenter. Most of the majorettes were from the wrong side of the tracks-- that may have been why I was attracted to them -- but Jean Brashear's father owned an automobile agency and that meant money. She and George Grinninger "ran off and got married" whenvthey were sophomores. It took Mr. Brashear's private detectives four or five days to find them in some motel outside, maybe, Altus, Oklahoma. They had the marriage annuled and George never had another date with Jean, as far as I know, and I double dated with George a lot.

I have no idea of Virginia Carpenter's family financial situation, but I suspect it was poor because she was always on the alert to push herself (I don't mean that critically; I admired her for it, but we seemed to recognize there was no potential in any personal relationship). I heard she married a Major in the Air Corps at Sheppard Field, probably before she was 20 years old; now THAT was upward mobility in the early 1940's. (Pat's sister, Barbara, attended a Wichita Falls Senior High School Reunion a few years ago and Virginia was there-- still petite and still blond, with a big smile and friendly).

There were MANY other girls in WFSH School that I thought were great and would have liked to have dated, but my work schedule limited my activity. (A car would have helped, too; the chances of seducing a 16 year old virgin in the back seat of a car with another couple in the front seat when you really didn't know what to do next were pretty slim. I know that one of the major problems today is teenage pregnancy, but in my day, it was teenage virginity).

There was a beautiful girl named Ellen Mitchell, who said in the Annual that what she wanted most was Friendship; I offered her a closer friendship than she had in mind. It seemed to me that the girls in High School were mostly attractive, and a lot were either gorgeous or had such great personalities that you overlooked their small imperfections. Most of the boys, on the other hand, came up pretty short and the ones who didn't probably had serious shortcomings that hadn't been discerned.

Football my sophomore year was spent, as expected, on the "C" Squad. I wasn't skilled enough and, especially, wasn't big enough to make the Rowdies my first year. In retrospect, most things I did almost guaranteed that I wouldn't be big enough. Running a mile before breakfast every morning, riding my bicycle a couple of miles each way to and from school, practicing football, then working (more bicycle riding) nights and weekends were not conducive to weight gain.

Football coaches and boxing trainers knew absolutely that weight lifting would make you "muscle bound" and unable to do anything else like play football or box. Even Charles Atlas's "Dynamic Tension" method of building muscle was discouraged. Fortunately, anabolic steroids, let alone their muscle building, bulking-up properties, had not been discovered. Weight work would have undoubtedly helped me; but I wanted so badly not only to play football but to be the very best that I would have gone the route with steroids while still in high school.

We "C" squaders played, as the sophomore teams in Texas high schools still do fifty years later, a full, formal schedule against Junior High Schools or "B" squads from smaller, neighboring high schools. We played our home games in Coyote Stadium and away games in the local high school stadium, complete with a full crew of registered, uniformed officials, cheer leaders and, usually, more spectators in attendance than I've seen as an official at many crucial varsity games on the East Coast and the Pacific Northwest. Early on, the coaches of “good old C Squad" decided to develop me as a left-handed tailback. The tailback was the equivalent of the quarterback in those stone age precursors (Single Wing, Double Wing and Short Punt formations) of the T Formation, with the "short man" the blocking back or spinner back who sometimes took the snap for handoffs on running plays, but the tailback was the "triple threat" man. He could take a pitchout from the short man for a run up the middle, off tackle or around either end, or he could take a direct snap from center and do all of the above and other exciting things as well, including quick kicking and, especially, passing the ball.

Those formations were so great for passing that the old "short punt" has been resurrected at every level, especially in professional football, as the "shotgun." Throwing left-handed was supposed to confuse all defensive backs, who were used to seeing tailbacks rollout to (except the newspaper writers called it "fade to" back then) the right before throwing a pass. As the

"Designated Left Handed Tailback of the future", unbelievable as it may seem, I was the subject of several articles on the sports pages of the two local newspapers.

I was magnificent in my first game, more than adequately covered by the press. I ran well, threw both to the right and really confused all the defensive backs, according to the sports writers, when I threw to the left, and even kicked the ball well (one of the sports writers theorized that a punt from a left footed kicker spiraled differently and was more difficult to catch). I went into the next game with even better coverage from the press. I threw ten passes, none of which were incomplete. Unfortunately seven were intercepted. With the passing game shot to hell, my running also suffered and I was rushed on the punts. Not too surprisingly, that game received minimal reporting and I was back at end the following Monday. One bad game and the world of football lost a potential All American Quarterback. I have mercifully been able to forget most of the rest of the season on the C Squad; that was the end of the road for a lot of aspiring football players, some of whom had been stars in Junior High. They were the ones who physically matured early and didn't get bigger, stronger, or faster in High School.

Most of us became "journeymen players" at the high school level; but one, Kenneth, "Rabbit" Parker eventually became an All-American linebacker at the University of Oklahoma. He had a minimum of ability and potential at the time, but was only 13 or 14 and kept saying "I'm going to stay here until I'm a star." We thought it was funny as hell at the time, but he REALLY did it. He spent his Junior year on the Rowdies with minimal playing time and his Senior year there with more success. With the change in rules by the Texas Interscholastic League that allowed unlimited eligibility prior to an 18th birthday before September1st, "Rabbit" Parker just kept coming back and playing until he did, indeed, become a star. Along with All State honors and a football scholarship to the University of Oklahoma, his nickname was upgraded from "Rabbit" to the more dignified "Cotton."

Fall football practice could not legally begin until August 1st. Often more boys went out for football (considerably more than one hundred) when practice began at WFSHS than were enrolled in most Texas high schools. Practices were intense, and kids were "cut" from the squad every day during the early sessions in August. Surprisingly, perhaps, when I read about the emotional trauma of aspiring professional football players trying to make their team, it reminds me of trying to make the team in high school. We were at the High School before 8:00 AM and weren't freed until late in the afternoon. Of course we had "TWO A DAYS"; the physical part of the morning session ended around 11:00 AM, then we would assemble in the "Football Study Hall" for a critique after which we were allowed to shower and eat lunch, followed by a welcome nap. By 2:00 PM we were back on the field and were kept there until the shadows grew long. Those afternoon practices were the character builders.

My Junior Year, as expected, I made the Rowdies. In retrospect, that was the most fun I had playing football. The coach was Bill Allen, one of the finest men I have ever known. (Later, he was a successful head coach at Paschal High School in Fort Worth, Texas.) I visited him a few times after I became a college professor; at least once he asked me to talk to his team in their "football study hall" and it was a thrill to be introduced as one of his former players who had become a college professor through hard work and studying.

We played all our games but the last on the road, always against the varsity of smaller towns in Class A or Class B. That meant we 14 to 16 year old kids were playing country boys who were up to 18 years old, except when we played in Oklahoma, where they could legally play until 21. Playing Wichita Falls (most local newspapers, conveniently forgot to mention we were not the varsity) was one of the big games of the year and always drew sellout crowds.

I played left end and started every game and played most of all of them; that's probably why it was the most fun season. My substitute was George Grininger, who made All District after I graduated and All Southwest Conference at Rice, but he didn't get to play much. The starting right end was R.C. West, and "Boots" Foster was one of the guards, both of them neighborhood friends and sandlot football teammates. Gene Hill was the quarterback; later he was All State, and, the last I heard, still holds the record for total offense in the State Championship Game. He was also the first freshman to play in the Cotton Bowl.

We had a lot of other quality football players on that team: Jimmy Castledine, who became the center after Willis Cates centered the ball into the end zone from the 30 yard line for a safety in a 0-2 loss in our second game; Jimmy eventually made All State and went to the University of Texas on a football scholarship. Bob Marshall went to Baylor on a scholarship, Bill

Boling to Rice along with George Grinninger; David "Mooneye" Green made it big at the University of Texas after the war. Charlie Hair, one of the toughest people I have ever known, dropped out of sight during World War II. I heard he was courts-martialled and sent to Leavenworth for dropping a potted plant on a naval officer from the mezzanine during a party. I have no verification of that, but it would not have been out of character. Charlie was a killer, with no respect for the human body--his own or anyone else's. It was not always comforting to have him on your side, but he and Moon Green, another of the toughest of the tough, did cause those older players to respect the kids on the Rowdies. It was a lot better to have them on your side than on the other side. I saw both of them knock opponents out cold on the football field and Charlie Hair in street fights even more often. Moon Green was as tough as Charlie, but not as vicious. Jimmy Castledine was probably tougher than either of them; he was the only person Charlie Hair was afraid of, but he didn't have the “Indian Sign” on Moon Green.

The main thing about that team was that we were a TEAM. Always the Visitors -- it was us against the world -- always younger, always smaller and NO FAN SUPPORT. Nobody from Wichita Falls went to our games, not students, parents or girl friends, even though most games were in nearby towns less than 50 miles away. We were the outlaws in black hats (we actually wore black uniforms with red numerals), the gunslingers imported by the rich ranchers in the range war. We HAD to stick together. Monday through Wednesday we scrimmaged against the varsity, the fabulous Coyotes, and were even more younger and smaller. The coaching staff magnanimously gave Coach Allen and us Thursday all to ourselves to prepare for Friday night's game. I scored the winning touchdown in the first game, against Jacksboro, by catching a 50 yard pass from Gene Hill on the last play of the game. The fact that J. D. Kirkpatrick, the left halfback, got credit for it in the newspapers the next day did not detract MUCH from the thrill.

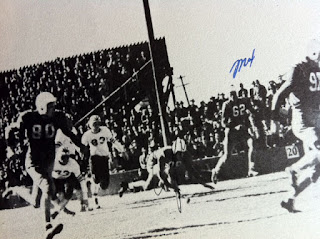

The next week was the infamous Willis Cates all-time long snap from center for a safety against Bowie, Texas. Ab Curtis (for many years supervisor of officials for the Southwest Football Officials Association) was the referee and, as time was running out and we had called a time out, came to our huddle and said "you have time for one more play." Gene Hill said "70 deep, go for the goal line and I'll get it to somebody". He threw it at least 60 yards, and I went up with two or three defensive backs and ended up with the ball. I can still remember squeezing the ball when I caught it so that it seemed all my fingers touched through the cover. I thought I had won another one for us, but when I came down I could see the goal line right in my face with the ball at least a foot short. We lost 2 to 0 and the next day's newspapers noted that, "even though the Rowdies lost 2 to 0, the most spectacular play of the game was a 50 yard pass to J. D. Kirkpatrick just short of the goal line as the game ended." Once was OK, but was twice in a row excusable? My mother didn't think it was and let the newspapers know her opinion. I learned from that to NEVER trust a newspaper reporter and it has stood me in good stead over the intervening years. I've been misquoted on the front page of the New York Times, in the Houston Post, the Washington Post and the Federal Register without a great deal of physic trauma, BUT WHY COULDN'T THE WICHITA DAILY TIMES GET IT RIGHT WHEN IT REALLY MATTERED?

We lost to Temple, Oklahoma 40 to 12. In Oklahoma, students could legally play until they were 21 (they weren't as smart as Texans so it took longer to finish school), but when Wichita Falls came to town they allegedly brought in "ringers" in their 30's; all the better players from the last decade suited up. I can't attest to the accuracy of those accusations; those kids from the sidelines yelling, "Nice Play, Daddy" may have been faking it just to intimidate us. I do know they had "Spec" Sanders, a hell of a running back, who later led the National Football League in rushing yardage. Once we met head on just after he took the hand off from the quarterback on a reverse, and we were both knocked out. After a timeout, we both stayed in the game--leaving the field for at least one play after an injury was not required back then. I could have been a

Team-mate of Spec Sanders at Cameron Junior College in Lawton, Oklahoma; they offered me a scholarship and I seriously considered going there. He later played for the University of Texas prior to professional football, unusual because most great University of Oklahoma and Oklahoma State football players played high school football in Texas.

The next week we lost, but were not beaten, to Nocona in the best game I ever had. I caught 10 of the 11 passes Gene Hill threw to me, most after my nose was broken in the third quarter. I missed one play while they put my nose back together from the outside with tape. I didn't score; R. C. West caught two touchdown passes after I had taken us down the field, but that was the strategy--they were double covering me and R. C. sneaked into the other side of the end zone all alone and caught the ball. Tall and skinny with mostly knees and elbows, he could do that very well even though he didn't do much after he caught the ball. When you catch it in the end zone you don't have to do much with it except hand it to the official or toss it to the ground. Innovative end zone theatrics such as spiking the ball, slam dunking over the crossbar, or dirty dancing after scoring never occurred to us. They were not then forbidden by the rules. My God, how impressive a Scalp Dance would have been in the end zone after I scored a touchdown.

Sad to say, we didn't lose to Nocona (the home of Nocona cowboy boots) because of the heroics of "Cowboy" Jack Crain. He was already establishing himself as the greatest broken field runner in the history of college football at the University of Texas. I had previously had the dubious pleasure of trying to tackle smoke in a Junior High School game against Nocona. His younger brother, Sam Crain, did a creditable imitation of the great one, but that was not what killed us. They had a great big fullback named Graham, who had a withered arm from polio, and they just kept running him at us. He used that crippled arm like a club, but he broke my nose with his knee. They just finally wore us down after we led 7 to 0 and 14 to 7. My mother was already asleep when I got home from the game and, since I didn't have any heroics to recount and wasn't anxious to explain my nose, I didn't wake her. Instead, she waked me with a piercing scream when she walked into my bedroom the next morning and saw my face. During the remainder of the night my upper lip had swollen to Ubangi-like proportions, turned purple and reverted to cover much of my upper face. I went to an Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat Specialist, paid for by WFHS to repair as much of the damage as possible. As he inserted gauze-wrapped, Vaseline-covered splints into both nostrils, he explained my breathing would probably not ever be the same again. HOW RIGHT HE WAS.

I insisted the Physician cover my face from the eyes down with a bandage; it was much like a white version of the veils worn by Muslim women. It shielded most of the damage, but both eyes were surrounded by tissue darker than that of any Arab beauty. I could hardly stand to look at myself and I didn't want anyone else to see my face. That was one of the tougher weekends at the Western Union, as I recall, and Monday at school was even worse. I was so ugly I didn't even cash in on the sympathy from the girls. However, practice was a lot easier; mostly I stood around. For our next game, against Holiday (I'm almost certain the setting of McMurtry"s "The Last Picture Show") I didn't distinguish nor disgrace myself in a 14-14 tie. The last, and only home game, was against Iowa Park. That one also ended in a tie (7 to 7) and the thing I remember most about it was that Coach Allen, in the pre-game talk, said some really nice things about how hard I had played, even when injured, and how tough I was; I was so carried away I cried. I was going to go out there and win that game by myself, if necessary. Iowa Park must have also had an inspirational player to dedicate the game to or an equally eloquent coach. Those Iowa Park players didn't show me any respect at all. Face masks were not part of the regular equipment, but after I broke my nose in the Nocona game, the Manager's developed a wire face protector that was remarkably similar to modern day face masks. Every time I caught a pass, those mean kids from Iowa Park would poke their fingers against my nose inside the protector when I was tackled. We ended up in a 7-7 tie in that one too -- so much for inspiration, motivation and the American Dream--maybe a Mexican Standoff is (if less than winning) better than losing.

Many years later I ran into Gene Hill at a football meeting in Galveston, Texas. I invited him and a lot of people I didn't know to my Town House for drinks. Gene started talking (I think Moon Green was there, too) about that Rowdie Team; he said something like "we played the varsities from all those schools and we were undefeated.". At the time I thought, "Gene, nostalgia has clouded your memory". Later I realized Gene Hill was absolutely right, we WERE undefeated; we were outscored a few times, but we were NEVER defeated.

During that Junior Year football season, the following Spring Semester, and the subsequent summer, I double-dated with fellow football players who met three criteria: they had access to a car, they asked me,and I could get off from work. Bill Bolin could get the family car about once a week; he went with Kathleen O'Brien, and I went with Marjorie Page until the O'Briens moved to Gainesville. I had "hung out" at the O'Brien home in earlier times; Mrs. O'Brien played the piano, any song you could think of, and we spent most of the time standing around the piano and singing. Mrs. O'Brien was more popular with most of the boys than Kathleen. Marjorie Page was the other candle flame that drew the male moths to the O'Brien hearth. I didn't know there was a Mr. O'Brien until Marjorie Page Kelly told me at least 50 years later. According to her, he stayed in a back room reading the newspaper and, probably having a few beers. Poor guy, there was no TV, so he couldn't even watch sports on the tube.

Later, Bill Boling and I dated Della Ground and Eileen Lopez. They had bad reputations because they "talked dirty"; we asked them for dates because we were sure they would be pushovers for a couple of football hotshots. I don't know what their track record was prior to or after our multiple encounters with them; but in horse racing parlance, "they still had their maidens" as far as we were concerned. They were so far ahead of us in all our contrived attempts at seduction that we all usually ended up laughing. Actually, Eileen was an attractive girl and, I suspect, pretty bright; I later regretted that I hadn't spent more time talking to instead of wrestling with her, but they were the ones who provided the come on. George Grinninger had his own car; his father had committed suicide a number of years earlier and he and a younger brother lived with their mother in a really nice but not ostentatious house in one of the better neighborhoods. His marriage with the flashy drum majorette annulled, he was dating a more staid young lady, Fairy Belle Kramer. I went with several girls, mostly with June Young who was a member of that social set; all the girls were visibly upset if I showed up with anyone else. Pair bonding started early in Wichita Falls High School, initiated and promulgated by the girls, with a lot of advice from their mothers. We dumb boys usually didn't have the slightest idea of what was going on; fortunately or unfortunately I figured it out with the Youngs.

During the Spring Semester of my Junior Year the Texas Interscholastic League issued a new rule that profoundly affected my football career and probably my life. Previously, football eligibility had been based on the number of semesters a student was enrolled in High School, with a maximum age limitation of, I believe, 19 at the time of participation. The new rule made

eligible anyone who had not graduated and whose 18th birthday was after August 31st. Born at 12:01 on September 1st you were eligible, even if you had already played three years. Parturition at 11:59 on August 31st and you were ineligible at 18, even if you had never played football previously and were a legitimate high school student.

The 1939 Coyotes were talented and the favorites to not only win the District Championship, but were given a shot at the State Championship. Among the seniors were the co-captains, Joe Parker and Henry Armstrong, and Max Bumgardner -- all of whom subsequently were All-American in college -- Smoky Huff, who was All Southwest Conference and 2nd or 3rd team All-American; and Billy Oglesby and Felton Whitlow who later played at North Texas State. They also had Curtis Holder, one of the greatest broken field runners I ever saw in High School football. However, they had a disappointing season, finishing 6 and 5 and didn't win the District Championship, even losing to Electra and Childress.

Largely because of their 1939 season, all of the above, except Curtis Holder and Joe Parker, plus several other seniors, elected to not graduate and return to vindicate themselves in 1940. I don't know whether Curtis Holder was caught by the September 1st Rule or was too intent on marriage to want to play more football; it was probably the latter, because he didn't go to college and dozens of schools ust have been after him. Unfortunately, colleges in those days did not sanctify marriage for their football players. I suppose the coaches and administrators preferred to hide their heads, ostrich-like in the sand, ignoring sex while their football players were taking advantage of their status to lay every willing female student available. Joe Parker could have returned, but he didn't have the time to spare. He graduated, went to the University of Texas, made All-American, graduated from Medical School, and joined his father in a highly successful medical practice in Wichita Falls. His father was our family physician for many years, and Joe was not only smarts but a nice guy and really tough for a rich kid.

Max Bumgardner was elected Captain at the Annual Football Banquet; that did not enhance my chances of beating him out as the starting left end the next season. R. C. West was not too happy that Billy Oglesby was returning at right end. We had in mind being the starting ends for the Coyotes the way it was on the Rowdies the previous year. We, along with several other Rowdies who were facing, if not glory, at least the well earned probability of being starters on the Coyotes realized we had been disenfranchised. It didn’t take a genius for those of us who would be eighteen before September 1st the next year to realize this was our last shot and our chances of recognition, major college football scholarships and even significant playing time ranged from slim to none. The returnees had all been starters, were more experienced, more mature, bigger, and more talented than we were.

The season was not a total disaster, but it was not what I had been working years for. I played some, always less than I wanted, mostly on defense which I much preferred. Fortunately, another new rule was unlimited substitution, so I got much more playing time than I would have under the previous limited substitution rules. Max was the captain, bigger and better than me, and I got mostly garbage time.

We opened, as usual, with Masonic Home at Coyote Stadium before a capacity crowd. Masonic Home was an orphanage for the children of deceased members of the Masonic Lodge. Their football team was known as “The Mighty Mites” because they were small and few in number and they had an unbelievably favorable press all over the state. Mostly they won (reputably they practiced 365 days a year) and when they lost, the newspapers made it appear that the winning team had, by sheer size and numbers, overcome the gallant “Mighty Mites.” My assignment in that game was to block DeWitt “Tex” Coulter who was 6’8” and weighed about 220 in high school. He was a REAL Mighty Mite; when I tried to block him, everything he hit me with hurt: elbows, knees, hands, helmet, hips; so much for the myth of the poor little orphan kids. They beat us on a late touchdown pass caught by Norman Strange who later became a close friend at A&M after the war.

The next week we lost to Breckenridge 20-7, and even though the two losses were not District games, the season was losing some of its promise. Some of those second-year seniors were probably wondering if they had wasted a year. I know some of us disgruntled second stringers noted we could have lost two in a row without their help and had a lot more fun doing it. Then we won the next eight, six by shutouts, with a scoring differential of 153 to 19. Needless to say, we won the District 2A Championship and were considered by most sports writers to have better than an even chance to win the State Championship.

Unfortunately, we had to play Amarillo at Amarillo. We went there several days before the game to practice and become acclimated to the change in altitude. We took the opening kickoff and got inside their 10 yard line before losing the ball on downs. We held them without a first down and after receiving the punt, took it in for a touchdown. We held on downs after the kickoff and were inside their 10 yard line when the first quarter ended. I guess the altitude got to us. Actually, I think we just got their attention; they had not been behind all season. The final score was Amarillo 42—Wichita Falls 7. They won the rest of their games, including the State Championship, without breaking a sweat. We saw the state championship game in the Cotton Bowl, via a chartered bus, courtesy of Wichita Falls Senior High School.

After the Bi-district Game, Coach Jefferies let us ride back to Wichita Falls on the special train; why not, we didn't have anything to lose. We were treated like heroes, even though we

had just had our butts convincingly kicked. However, after cuddling up with our girl friends, regular or newly found, the aches, pains and disappointment gradually diminished as we

descended to lower altitudes. Bold souls who removed all the light bulbs in the coaches greatly aided the transition.

That was the end of high school football for me, but most of the guys I had played with on the Rowdies were young enough to return the next season and they went undefeated and unworried to win the state championship. George Grinninger, my substitute on the Rowdies

and 3rd string my senior year, made All District and Troy Stewart, who was on the Rowdies the previous year, made All State. I lost out on two counts: by the eligibility rule change and being born on July 31st rather than September 1st.

Actually, Troy Stewart was hurt more than anyone I knew by the September 1st rule. I don't know whether he was a slow learner (his knickname was "Hoss" because of his strength and

speed) or had dropped out of school during the depression to work, as many kids my age did, but he played on the Rowdies as a sophmore, made All State as a junior but was ineligible to play

his senior year because he was 18 before September 1st. He accepted a football scholarship at Schriener Institute, in Kerrville, Texas, a military school from first grade through two years of junior college. I never heard anything about him again; if he could have played his senior year at Wichita Falls High School, he would have gone to a major college and probably played

professional football.

Coaches from several colleges in the Lone Star Conference, other small colleges, and numerous junior colleges offered me scholarships. Several interviewed R.C. West and me together in my family’s living room and offered us a package deal; they wanted both of us. But R.C. wouldn’t go unless I did, and I was determined to go to Texas A&M.

I elected to not graduate at mid-term; instead I took one course the spring semester of 1941 and worked the rest of the day at the Western Union. That gave me a lot more time for social activities; every night was free and I had more money than those of my friends who depended on allowances (I NEVER had one) or sacking groceries at a grocery store. I could shoot pool, drink beer, and go on dates and not worry about time, money or football.

R.C. West and I double dated for our High Graduation, Banquet and Dance. My date was Ann Kring, daughter of the Manager of the Chamber of Commerce, and his was a girl named Pat George whom I had noticed previously because of the way she filled out sweaters. She was a late transfer from Abilene High School and wasn’t part of the in crowd. I stabbed my buddy in the back and had a date with her for the next day before we took our dates home. I don’t know what happened to Ann Kring after that; I had a new and consuming interest.

No comments:

Post a Comment